Economists typically assume that firms are sophisticated and make optimal decisions. Yet, in practice, firms often make mistakes. This study asks why: Do firms know the right action but fail to implement, or do they lack knowledge of the optimal action?

To explore this question, Strulov-Shlain examines a 2014 Israeli reform that banned prices ending in denominations of coins that no longer existed, in this case the equivalents of the U.S. penny and nickel. The change forced supermarkets to round prices to the nearest 10 Agorot (e.g., 2.90 or 3.00).

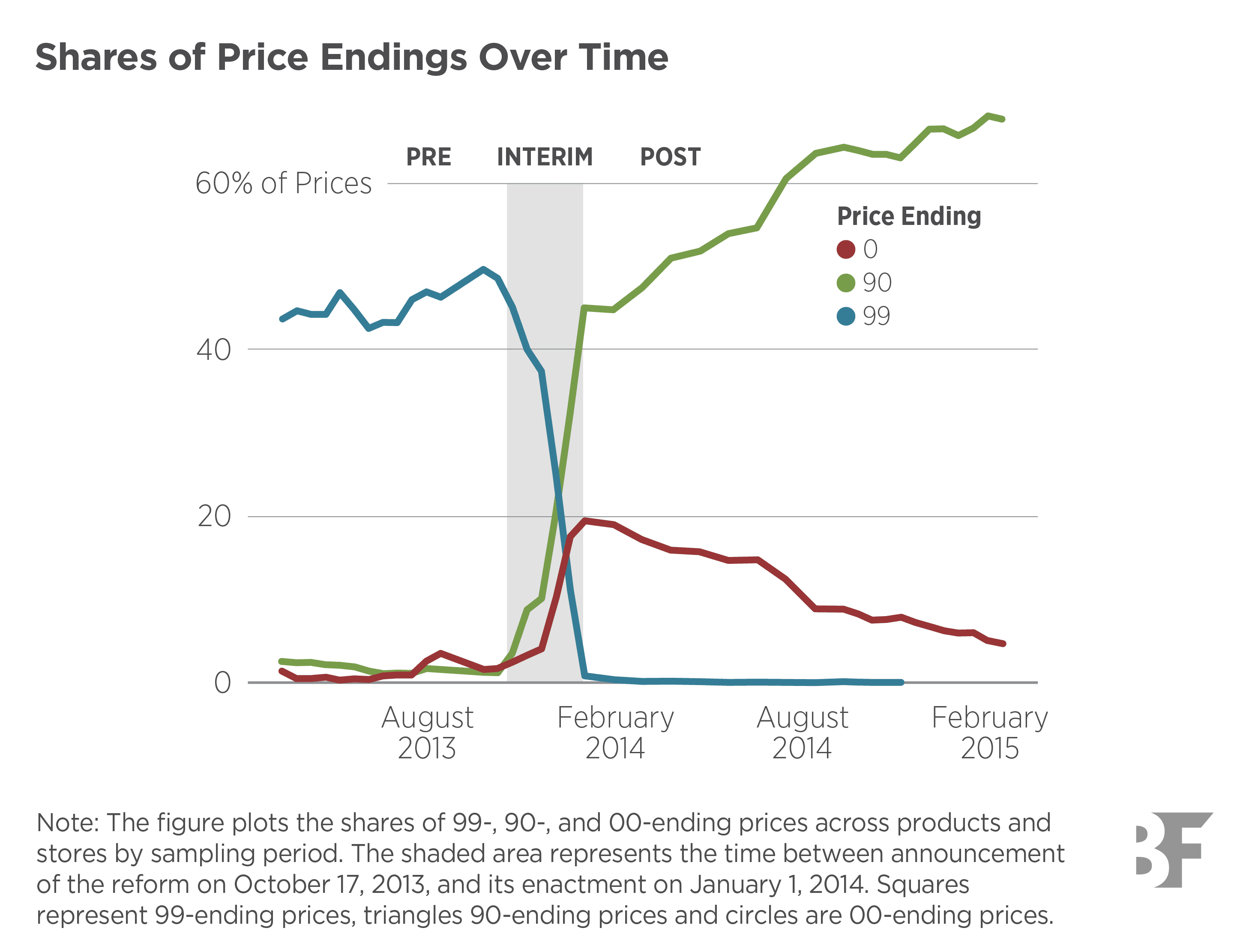

Importantly, the reform eliminated the possibility of “99” endings, which are optimal due to left-digit bias (the tendency for consumers to overweight the leftmost digit in a price). In this way, the reform created a natural experiment: Could firms predict the new optimal price endings?

Strulov-Shlain uses data covering supermarket prices and transactions from 2013 to 2015 to examine prices before and after the reform. He also measures how “crossing the left-digit threshold,” e.g., changing a price from $4.99 to $5.00, affects demand.

He finds the following:

- Before the reform, roughly 45% of supermarket prices ended in 99, the optimal ending under left-digit bias, while nearly none ended in 00. This suggests firms were partially knowledgeable about optimal pricing.

- When prices ending in 99 were banned, about 40% of prices moved to 90-endings (the new optimal format), but 20% shifted to 00-endings, crossing the left-digit threshold. This suggests that firms lacked full knowledge of how left-digit bias would translate under new pricing.

- Crossing the left-digit threshold was costly. Changing a product’s price from 4.99 to 5.00 reduced demand by 5-9% compared to changing it to 4.90. Despite this sizable effect, many firms initially adopted suboptimal 00-endings, suggesting that mispricing was due to lack of knowledge, not inability to implement.

- The share of 00-ending prices fell from roughly 20% immediately after the reform to 5-8% within a year, and around 3% by 2018–2019. Some retail chains exhibited abrupt, “light-bulb” shifts rather than gradual adjustment. At the product level, once prices moved to 90-endings, they tended to stay there, while those initially set to 00 rapidly reverted to 90. Products that transitioned from 00 to 90 were 15 times more likely to remain at 90 than revert, suggesting incremental learning through experience.

- To quantify the implications of these behavioral patterns, Strulov-Shlain builds a model that translates the estimated demand responses into optimal pricing prediction. He finds that firms lost about 0.75 percentage points in profit immediately after the reform due to mispricing but recovered within a year as they adapted. By the end of the adjustment period, average pricing efficiency exceeded pre-reform levels, suggesting genuine learning rather than mechanical adaptation.

These findings challenge the standard economic assumption that firms effectively optimize, suggesting instead that partial knowledge should be treated as a benchmark for firm behavior. The mechanism sustaining partial knowledge appears to be insufficient exploration. Had firms experimented more extensively with different price endings before the reform, they would have learned the full structure of demand. For researchers, these findings encourage taking partial optimization seriously when modeling firm behavior. Assuming full optimization may lead to incorrect predictions about how firms respond to regulatory changes or market shocks.