Few areas of economic research have attracted as much attention in recent decades as issues surrounding social mobility, both among researchers and policymakers. Even as economists argued about causation (does moving to a new neighborhood, for example, reduce intergenerational poverty, or does selection bias explain positive outcomes?), policymakers initiated programs to help Americans move.

However, social mobility has long been a feature of western economies, though the drivers of that mobility have changed over time. This is especially true of the dramatic impact that the Industrial Revolution: a period of rapid technological advancement beginning in Great Britain in the mid-18th century, that transformed economies from agricultural and handicraft-based systems to those dominated by machine manufacturing and large-scale factories had on the traditional “ society of orders: the system of social organization in pre-industrial Europe that divided society into a rigid hierarchy of status groups, where an individual’s position was determined primarily by birth and fixed by law and custom ,” which divinely ordered allocations of people into separate parts of a hierarchy, and which existed in English society in the centuries leading to the transformative 18th century and beyond. The authors of this new work are the first to empirically conceptualize the society of orders, which allows them to examine its consequences for social mobility over time.

Prior to the Industrial Revolution, English society was shaped by a rigid social hierarchy where people’s wealth and status were largely predetermined by birth, noble titles, and family surnames. Medieval society was composed of three orders, those who work, pray, and fight, with surnames often indicating specific occupations that sons would inherit from their fathers (Smiths were blacksmiths, for example, Millers ground wheat, Bakers baked bread, and Coopers forged barrels). Also, surnames largely indicated, if not determined, societal status (children born into such surnames had no chance to rise above their station). That this “great chain of being” was ordained by God ensured that people kept their place, at least until the onset of an unexpected economic “miracle” broke those chains.

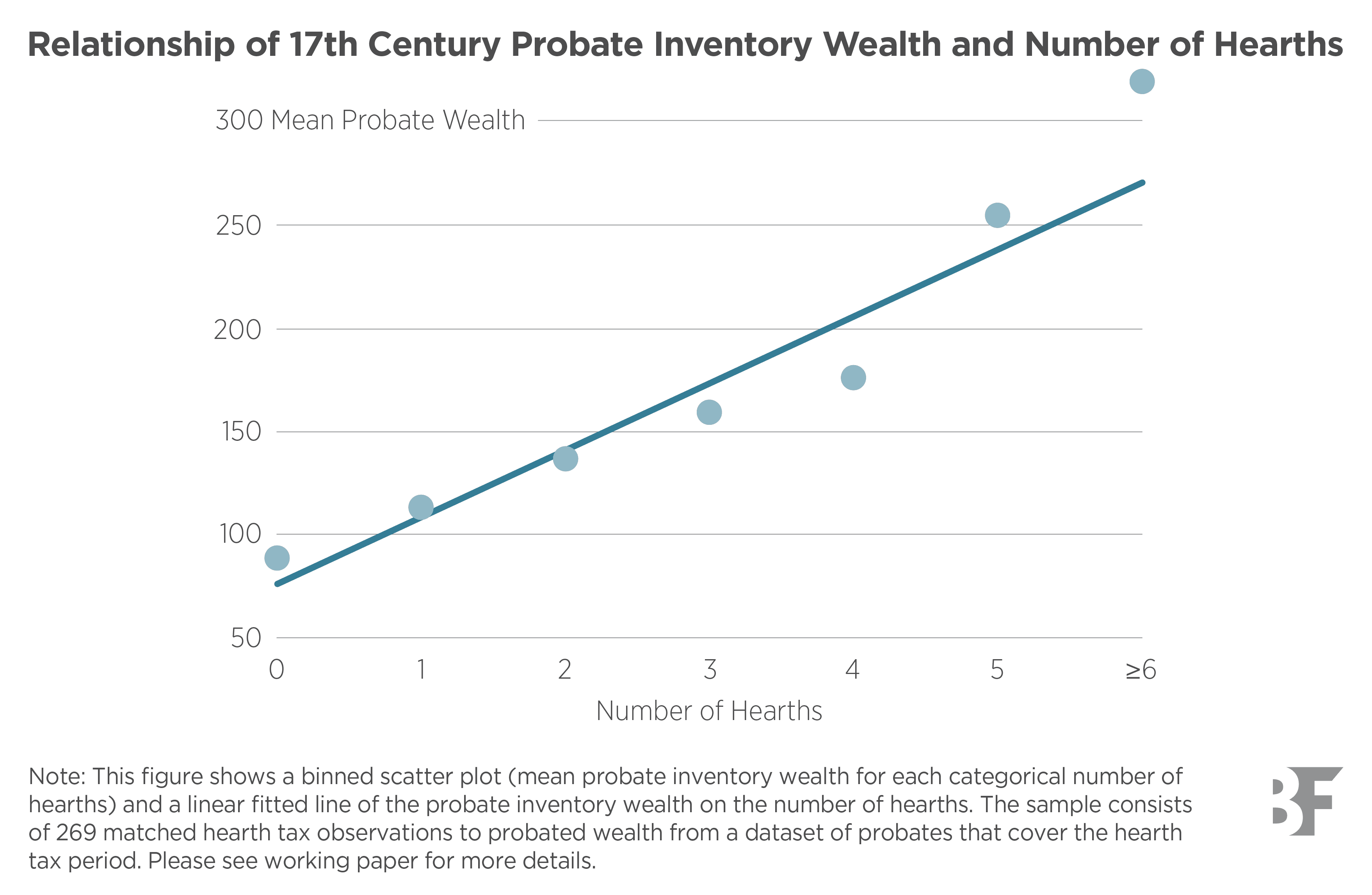

To investigate the impact of the Industrial Revolution on English society, the authors assembled two unique historical datasets: their pre-Industrial Revolution data consists of hearth tax returns from 1662-1674, which recorded household wealth based on the number of fireplaces, covering 343,022 heads of households across 26 counties, while their post-Industrial Revolution data includes digitized Principal Probate Registry records from 1862-1899, documenting the wealth of deceased persons who held at least 5 pounds at death. Both datasets include individuals’ names, titles, and locations, allowing the researchers to analyze how well traditional social markers predicted wealth distribution across these two periods. They find the following:

- Before the Industrial Revolution, being a member of the nobility: the highest-ranking aristocrats, whose titles were often inherited and whose ranks, in descending order, were duke, marquis, earl, viscount, and baron or gentry: a class below noble that included landowners, knights, baronets, and esquires, often living on rental income from their estates and often held local positions like justices of the peace explains 17% of the variation in the share of wealth individuals owned, afterwards it explains only 6%, a decline of two-thirds.

- Family surnames, which historically carried strong occupational and status associations, explained 10% of wealth variation in the pre-industrial period but only 6% afterward.

- This breakdown was not uniform across England but was most pronounced in regions that experienced greater industrialization. In heavily industrialized areas, the explanatory power of surnames for wealth distribution fell to essentially zero, while in less industrialized regions, surname-based wealth prediction remained constant at around 10%.

The authors conducted benchmarking exercises to confirm that these data do, indeed, represent a breakdown of traditional society and not just statistical noise. They reveal that before the Industrial Revolution, the existing social hierarchy captured about 41% of its theoretical maximum explanatory power for wealth distribution, suggesting a society where traditional orders still significantly influenced economic outcomes. After the Industrial Revolution, this figure plummets to less than 10% of the theoretical maximum.

The authors also investigate the extent to which different attributes predict whether a person will be wealthy, or in the top decile of the wealth distribution. Essentially, the Industrial Revolution has little impact on the probability that a noble is rich, while the probability that a member of the gentry is wealthy increases significantly. The authors interpret this effect on the gentry as reflecting the flexibility of this tier of the society of orders. As the economy grew, new entrants were naturally wealthier than incumbents who were less able to take advantage of new economic opportunities.

This research also addresses two questions relating to geographic mobility and social mobility: Where did people with socially mobile surnames tend to end up geographically and within what economic sectors; and what were the characteristics of socially mobile parishes: fundamental administrative units for both religious and secular purposes, centered around a church and its priest, that served as the primary unit for managing local taxes, poor relief, and maintaining public infrastructure like roads and bridges ? They find that:

- People with socially mobile surnames, or those showing increased wealth dispersion within family lines, were significantly more likely to migrate to northern England and find employment in manufacturing industries.

- For parishes, those that experienced more mobility were likely urban, had an institutionalized market prior to the Industrial Revolution, were less agrarian, and had lower income levels.

- Initial social structure was key, with mobility associated with having more gentry and fewer yeomen: members of a rural middle class, ranking below the gentry, who typically owned and cultivated their own land, but also included skilled employees such as manor bailiffs, constables, and household servants , which were a class of wealthier landowning peasants.

- Political characteristics are also significant: parishes including a member of Parliament are more mobile.

The implications of this research extend beyond historical curiosity to inform our understanding of social mobility more broadly. By focusing on the general population, the authors show that the Industrial Revolution fundamentally altered the relationship between family background and economic outcomes. Likewise, this work challenges narratives that focus solely on the Industrial Revolution’s negative social impacts, suggesting instead that this period may represent a “dawn of liberty” for those previously entrenched in rigid social hierarchies. In doing so, this research contributes to ongoing debates about the relationship between economic development and social mobility, showing how a major economic transformation can weaken traditional status-based systems and create new pathways for advancement.