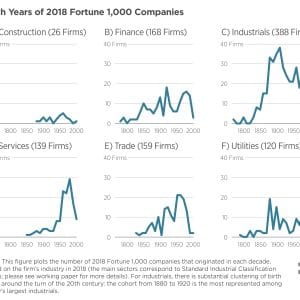

Since the 1970s, stagnating average earnings and rising earnings inequality in US labor markets have spurred academic research and fired policy debates. This issue has only intensified in recent decades as attention has focused on the plight of male workers in industries and regions facing economic decline. Despite this interest, existing research has provided little insight into trends in lifetime earnings, offering only point-in-time analysis of annual incomes.

In a first-of-its-kind study, this paper addresses this gap by constructing measures of lifetime earnings for millions of individuals using a 57-year-long panel (1957–2013) from US Social Security Administration (SSA) records. The authors’ lifetime earnings measure is based on 31 potential working years between ages 25 and 55, which allows them to construct lifetime earnings statistics for 27 year-of-birth cohorts. The oldest cohort turned age 25 in 1957, and the youngest one turned age 55 in 2013, the last year of their sample.

The authors examine how lifetime earnings of the median male worker changed from the first cohort (1957) to the last (1983). [They also examine changes in women’s roles in the labor market over this period. See related Research Brief.] Their analysis reveals the following key fact: The lifetime earnings of the median male worker declined by 10% from the 1967 cohort to the 1983 cohort. Perhaps more strikingly, more than three-quarters of the distribution of men experienced no rise in their lifetime earnings across these cohorts. Accounting for rising employer-provided health and pension benefits partly mitigates these findings but does not alter the substantive conclusions.

How are these changes reflected in wage/salary earnings? When nominal earnings are deflated by the personal consumption expenditure (PCE) deflator, the annualized value of median lifetime wage/salary earnings for male workers declined by $4,400 per year from the 1967 cohort to the 1983 cohort, or $136,400 over the 31-year working period. (When the authors adjusted for inflation using the consumer price index, the decline in median male lifetime earnings is nearly twice as large.)

For policymakers, these findings are sobering, and important. For example, the authors show that newer cohorts of workers were already different from older ones by age 25. Once in the labor market, the earnings distribution for these newer cohorts evolved similarly to those of older cohorts. Further, the authors’ findings suggest that the sources of the dramatic changes in the US earnings distribution over the last 50 years may be found in the experiences of newer cohorts during their youth (and possibly earlier). To illustrate, please see Figure 2, which reveals that the decline in median earnings at age 25 continued until 1993, after which time there was a brief resurgence followed by another period of decline. In 2009, median earnings for 25-year-old males were at their lowest point since 1958.