Economists have long pondered the drivers of productivity: How is it that some firms produce more than others, using the same inputs? One set of explanations points to the role of measurement—different data and methodologies simply yield different estimates of productivity. Another set points to management—certain firms are more productive because they are better run. Yet, even when firms are managed similarly and measured consistently, some productivity differences persist. Motivated by this puzzle, this paper considers a new determinant of productivity: the quality of financial reporting.

Unlike publicly traded firms, which must produce audited financial statements, private firms choose their own reporting standards. These standards range from basic compilations to full external audits. This variation creates a natural laboratory for studying whether and how financial measurement quality affects productivity.

The authors study the relationship between productivity and financial reporting quality using three data sources. From the 2021 Management and Organizational Practices Survey (MOPS) by the U.S. Census Bureau, they collect information on management practices and financial reporting at manufacturing establishments. From the IRS, they obtain tax returns covering all medium and large private firms, which detail both production activities and accounting choices. And from Sageworks, a financial technology company, they gather financial records on smaller private firms.

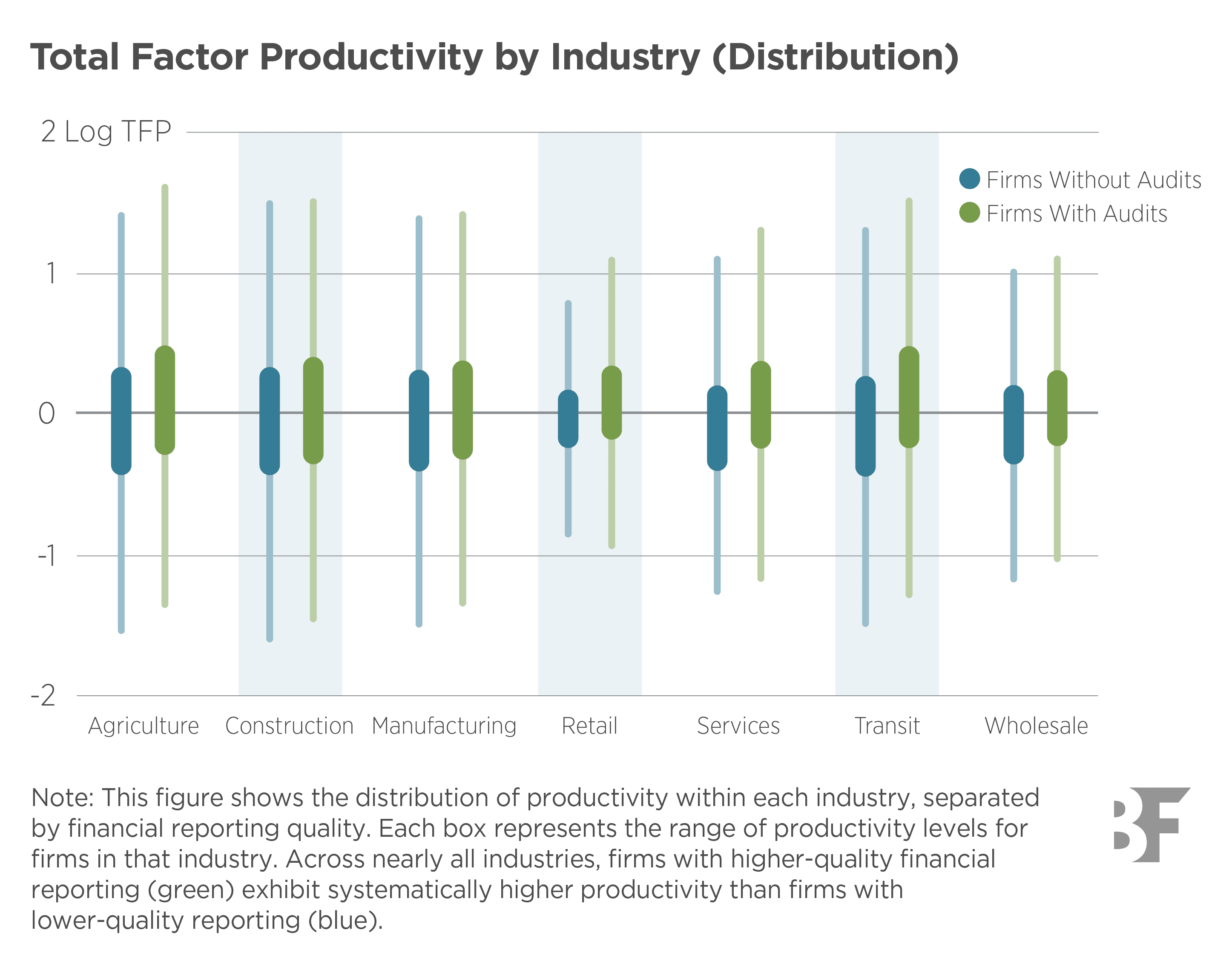

Using these datasets, the authors estimate how much each firm produces relative to its inputs, a measure called total factor productivity: a measure of how efficiently a firm converts inputs (labor, capital, and materials) into output, capturing productivity improvements beyond changes in input usage . They then examine whether firms with higher-quality reporting are systematically more productive, even after accounting for management practices. They find the following:

- Different firms within the same industry exhibit substantially different levels of productivity. In manufacturing, for instance, the most productive plants produce nearly twice as much output as the least productive plants, using comparable labor and capital.

- Within the same industry, more productive firms consistently have higher-quality financial reporting standards, while less productive firms have lower-quality standards. Across all three datasets, differences in reporting quality explain 10-20% of the productivity gap between high- and low-performing firms, comparable to the explanatory power of management practices, information technology, and human capital.

- Management practices alone do not explain the audit results. Instead, audits and management practices reinforce each other: firms that combine strong management with audited financial statements are about 2 percentage points more productive than would be expected from either practice on its own.

Building on these results, the authors next consider mechanisms that could explain the association between productivity and reporting quality. They find the following:

- Audits deliver the greatest value in instances where accurate operational information is most critical for decision-making, thereby reinforcing their role as a managerial technology. For example, the productivity effects are strongest in highly competitive industries with thin profit margins, where even small efficiency gains matter. In contrast, the benefits are weaker in research-intensive industries where long-term innovation drives growth. Younger firms also see larger gains from audits, suggesting financial reporting quality plays a particularly important role when internal management systems are still developing.

- Firms with audits are 7 percentage points more likely to survive over a two-year horizon when compared to firms with weaker financial reporting practices, even after accounting for their baseline productivity levels. This survival advantage is larger among smaller firms, again suggesting the role of financial reporting as a managerial technology.

- The timing of productivity gains reveals how audits work. Firms show no significant productivity increase in their first year of being audited, but see substantial gains in the second year. This pattern suggests audits improve managerial decision-making over time rather than simply correcting biased reports immediately.

- Exploiting variation in state tax rates, the authors find that the productivity advantage of audited firms is nearly twice as large in high-tax states like California compared to low-tax states like Texas. This indicates that audits constrain firms’ ability to underreport output to minimize taxes, reducing artificial productivity differences across firms.

A large body of research shows that management practices such as goal-setting, performance monitoring, and employee incentives function as technologies that systematically improve firm efficiency. This paper extends this work by identifying financial reporting quality as another distinct managerial technology. The authors show that audits are not merely passive records of economic activity but information production technologies that shape firm performance. Investment in high-quality financial reporting, therefore, is not simply a compliance requirement but a strategic decision comparable in impact to other core management practices.