Making policy entails setting rules, regulations, and other guidelines with a desired outcome in mind. However, people respond differently to such efforts, and these heterogeneous responses necessarily complicate a one-size-fits-all approach to policymaking. But what if we could personalize policy? What if we could tailor a policy to individual characteristics and, thus, improve policy outcomes?

Such an effort is challenging, in part, because policymakers cannot observe everyone’s behavior or type. Further, when people’s objectives diverge from the policymaker’s, individuals may strategically misreport their types. This information problem makes it harder for the policymaker to personalize policies effectively.

This paper uses a field experiment to test whether policies can be designed to overcome this information problem and, thus, effectively personalize policy. The authors consider a policy that uses financial incentives to influence behavior. Such policies are increasingly common in such sectors as education, the environment, and preventive health. For example, a workplace may incentivize participation in a step count program to improve health outcomes. However, one step plan likely does not fit all participants, with high walkers needing a higher step count and low walkers benefitting more from a lesser goal. If participants were all assigned a personalized goal based on their reported step counts and given $5 to reach their goal, it is easy to imagine certain participants choosing to misrepresent their step count to manipulate their assigned goal. For example, high walkers might falsely report a lower step count to get a lower goal and an easier time earning the incentive payment, and so everyone would end up with the program with the low step count.

Mechanism design: Focuses on designing rules, or “mechanisms,” that incentivize individuals to reveal their private information and achieve desired outcomes, even when those individuals act in their own self-interest. In other words, you start with a desired goal and work backward to create a system that achieves it. , wherein participants are given a menu of contracts designed to incentivize choices that align with a policy’s objectives, approaches a solution to this predicament. From our example above, that could mean offering one contract with higher goals and higher payments, and another with more modest goals and lower payments. In this case, the higher payment could induce the higher walker to choose the contract with the more ambitious goal, while the low walkers would choose the less ambitious contract, thus allowing the policymaker to achieve personalization. Such programs are considered “ incentive-compatible: In game theory and economics, incentive compatibility refers to a situation where individuals have an incentive to reveal their true preferences or act in a way that aligns with the desired outcome of a system or policy. Essentially, it means that the mechanism is designed in such a way that it is beneficial for individuals to be truthful. ,” in that they ensure that participants have an incentive to choose the contract that aligns with the policymaker’s objective.

The authors employ mechanism design to personalize a policy that encourages exercise among 6,800 urban Indian adults to address diabetes, hypertension, and their precursors. Participants were provided pedometers and incentives to meet daily step targets. The authors personalized their program by allowing some participants to choose their incentive contracts from an incentive-compatible menu where contracts with higher step targets featured higher incentive payments. They randomly assigned participants either to a treatment group, or the Choice group; to one of three Fixed groups that each received a uniform (not personalized) step target; or to a Monitoring group that received a pedometer but no incentives. They find the following:

- Choice almost doubles the effectiveness of the incentive policy relative to a uniform, intermediate step target. The Choice treatment increases walking by roughly 4 additional minutes per day, an 80% improvement that both the medical literature and the authors’ experimental data suggest is likely to yield meaningful health impacts.

- The Choice treatment achieves this increase in walking without an increase in payments. Moreover, Choice yields gain across the full distribution of walking; that is, Choice achieves the gains of the low target at the bottom of the distribution and of the high target at the top but avoids the downside of “neglecting” one part of the distribution.

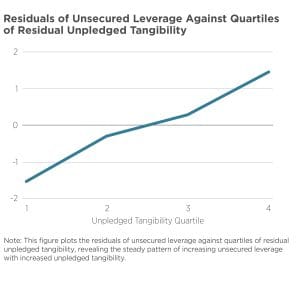

- Consistent with a standard mechanism design model, the Choice menu is effective because participants sort into contracts in a way that is advantageous to the principal. Specifically, the authors empirically confirm the theoretical prediction that a principal would prefer to assign higher step targets to participants who walk more in the absence of incentives (i.e., who have higher “baseline steps”) and lower targets to those who walk less, as higher step targets generate relatively more steps (but not more payments) from participants with higher baseline steps. Moreover, participants with higher baseline steps choose higher step targets on the menu.

Bottom line: Choice matters. When offered an incentive-compatible menu, many participants prefer the contract that increases their steps most, relative to their payments. This finding has wide implications. Similar incentive-compatible menus could be used to incentivize other beneficial behaviors, such as schooling, R&D by firms, or the adoption of eco-friendly technologies. Incentive-compatible menus could also personalize other types of policies besides incentives, including unemployment insurance, where such menus could enable participants to balance the duration of benefits against the payout levels, sorting based on their underlying employability.