A growing literature in economics studies the multifaceted relationship between religion and development. One of the most enduring debates in this field concerns whether economic development inevitably leads to religious decline. The traditional secularization hypothesis predicts that economic growth and modernization lead to declining religious belief and practice—a pattern observed in many Western societies.

In this paper, the authors challenge the secularization hypothesis. Rather than waning, they argue that religious beliefs, practices, and institutions may be adapting to the profound social and economic changes sweeping across the globe. In addition, the authors posit that non-Western societies may be leading some of the trends observed in terms of religious innovation worldwide, including the rise of highly decentralized religious movements which coexist and compete with well-established major denominations and secular institutions. The authors use empirical evidence to support these hypotheses while reviewing how recent scholarship explains the persistence and adaptation of religion in developing contexts.

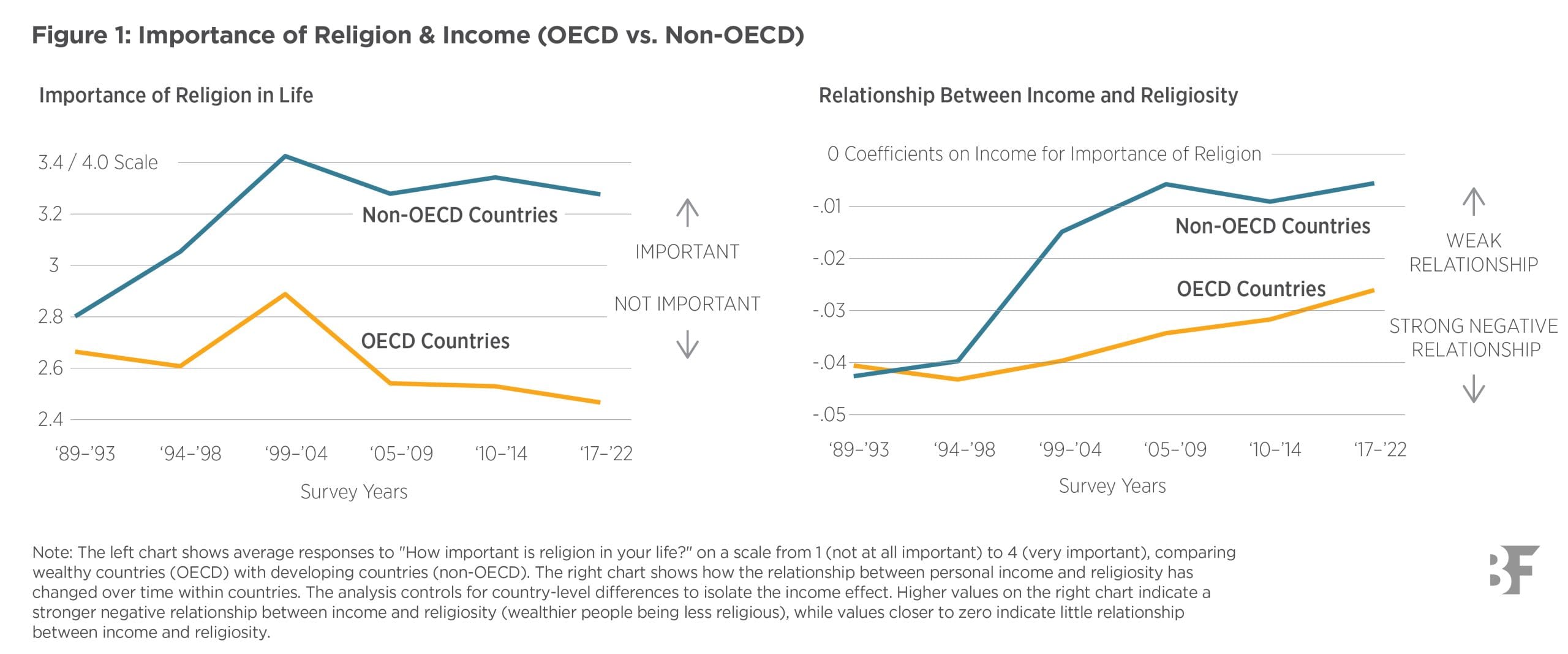

The authors analyze six waves of World Values Survey data covering 433,181 observations from 108 countries between 1989 and 2022, complemented by Pew Research Center data on religious beliefs in sub-Saharan Africa. They examine trends in religious importance, service attendance, and beliefs across different regions and income levels, distinguishing between OECD (high-income) and non-OECD (developing) countries to document the religious divergence. The analysis incorporates both major world religions like Christianity and Islam, as well as traditional belief systems that often coexist with formal religions in developing regions. They begin by documenting the following:

- Respondents in the MENA region, sub-Saharan Africa, and South/Southeast Asia are most likely to report that religion plays an important role in their life and to frequently attend religious services. The self-reported importance of religion and frequency of religious service attendance have not declined in these regions since the 1990s, while Latin America displays stable trends and former communist countries are experiencing a resurgence of religion.

- Unlike survey respondents in OECD countries, respondents from non-OECD countries report a sharp increase in the self-reported importance of religion in life: In 2017-2022, 88% of respondents in non-OECD countries reported believing in God compared to 67% in OECD countries, 76% believed in heaven compared to 53%, 56% prayed daily compared to 30%, and 36% attended religious services weekly compared to 20%.

- The magnitude of correlation between income and religiosity has been declining over time, with emerging and developing countries (EDCs) leading this trend. Since the 2010s, the correlation between religiosity and income (conditional on country fixed effects) is close to zero in EDCs, while OECD countries are converging toward this pattern.

- Traditional belief systems coexist with more formal religions in many EDCs. Using data from sub-Saharan Africa, 43% of individuals report believing in witchcraft on average, 42% believe in the evil eye, 48% believe in evil spirits, 19% own traditional sacred objects, and 15% participate in ceremonies to celebrate ancestors.

- Even where over 90% of respondents report affiliation to a major transcendental religion (e.g., Islam or Christianity), a large majority also believe in witchcraft as a causal logic for misfortune. This demonstrates widespread religious syncretism where individuals hold multiple religious beliefs rather than transcendental religions displacing traditional practices.

What explains these results? The authors review recent literature to understand what drives continued religious adherence in emerging and developing countries. They identify two broad sets of mechanisms that explain why modernization has not uniformly reduced religiosity in these settings: economic insecurity and mutual aid, and identity and adaptation during cultural transitions. They draw the following conclusions:

- The literature identifies religion as a source of security. Research shows that higher GDP has not eliminated income volatility and financial insecurity in many EDCs, which are characterized by exposure to shocks, conflict, and weak institutions. Studies demonstrate that this drives people to seek religion for both risk management and psychological comfort. Research has shown that negative economic shocks, climatic disasters, and conflict exposure increase religious adherence. The literature reveals that religious networks provide both spiritual comfort and tangible mutual aid where formal welfare systems are weak. Experimental evidence from Ghana demonstrates that formal insurance can crowd out religious giving, revealing systematic substitution between formal coverage and what researchers term “God insurance.”

- The literature also shows that religion serves as a source of cultural identity during transitions. Research demonstrates that religion serves as an anchor for identity during periods of rapid social and economic change, including urbanization, migration, and political upheaval. Studies document that religious communities provide not only spiritual comfort but also ready-made social networks, job information, and informal insurance for urban migrants. The literature from Latin America, Egypt, and South Asia demonstrates how religious movements grow during periods of economic dislocation and cultural transition, offering migrants supportive identities and helping individuals cope with unfulfilled aspirations.

- Finally, the literature documents religious institutions as competing service providers. Research shows that in many EDCs, religious institutions operate as powerful competitors to secular state institutions, delivering education, healthcare, and financial support where government capacity is lacking. Studies document that this creates enduring “dual” institutional systems where religious organizations often command superior legitimacy and trust compared to state agencies. The literature demonstrates that religious institutions also compete like firms in a marketplace, adapting their doctrines, pricing, and service provision in response to economic conditions and policy changes.

These findings reveal that development policies must account for religion’s enduring and adaptive role rather than assuming secularization. Religious institutions often operate in parallel with or in place of state services, meaning their responses can determine whether development programs succeed or fail. Policymakers should recognize that religious actors command superior legitimacy and trust in many contexts, making partnerships rather than competition more effective for service delivery. Understanding religious competition and adaptation is crucial for predicting how communities will respond to economic opportunities, social programs, and institutional reforms.

Written by Abby Hiller • Designed by Eric Hernandez