Field experiments: A study conducted in a real-world setting where researchers manipulate one or more independent variables to observe the effect on an outcome of interest. are widely regarded as the gold standard for uncovering the true impact of many policies. Recent advancements in experimental methods have enabled an unprecedented ability to understand what works, what doesn’t, and why. Despite their promise, however, field experiments have seen limited adoption among policymakers.

In this paper, the researchers tackle this “uptake problem,” which they propose stems from two key challenges: First, concerns about scalability can erode confidence in scientific findings, as many programs that succeed in experimental settings struggle to deliver comparable results at scale. Second, the inherent uncertainty of experimentation can impose costs on policymakers, particularly when results diverge from expectations.

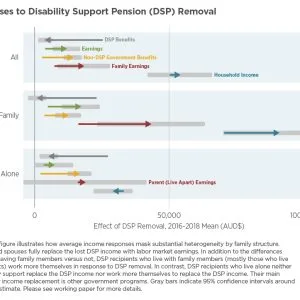

Note: This figure illustrates policymakers’ predictions for the outcomes of both a pilot intervention and a full-scale intervention. The points are color-coded to distinguish whether policymakers learned about the pilot results before making their predictions for the full trial. As you can see, policymakers who were not exposed to the pilot results tend to maintain consistent expectations between the pilot and trial outcomes, while policymakers who were informed of results overwhelmingly anticipate null results: When a study or experiment does not find a statistically significant effect or relationship between the variables being tested. This means the data does not provide evidence to reject the null hypothesis (the assumption that there is no effect or relationship). for the full-scale intervention.

To test these concerns, the authors design an experiment in which they study how policymakers respond to unexpected or counterintuitive findings. Their approach is twofold. First, they implement a field experiment to assess the efficacy of a commonly used intervention in higher education. Second, they investigate how policymakers—and the broader public—respond to the results.

The authors’ field experiment evaluates the impact of small financial incentives designed to increase participation in college savings accounts, a policy intervention implemented in most states but not previously tested experimentally. The incentives are premised on the idea that small financial rewards can increase program attractiveness and help citizens outweigh the burden of sign-up costs. The results are unexpected, however: In their trial, financial incentives did not significantly improve participation in college savings accounts.

The authors then conduct a survey experiment with a sample of policymakers responsible for administering college savings accounts and similar state-run savings programs, as well as with a representative sample of the US public. The survey elicits respondents’ predictions for the experimental outcomes and gathers their opinions on policy experiments. During the survey, a randomly assigned treatment group is informed of the actual experimental results. The authors compare the responses between the treatment and control groups and find the following:

- Policymakers who are randomly exposed to the trial results report a reduced focus on scaling the trial and an increased interest in funding new evaluations.

- Learning the trial results also causes policymakers to question both the efficacy of similar interventions in other contexts, and even the scientific approach in general.

- The authors identify similarities between their sample of US citizens and policymakers. For example, like policymakers, the public is (even more) optimistic about the potential for financial incentives to improve program participation rates. Additionally, when the public learns the results, they state remarkably similar preferences for how resources should be re-allocated between scaling and further evaluations.

- The authors also find dissimilarities between citizens and policymakers. For example, unlike policymakers, the public maintains their high support for policy experiments even after learning of the disappointing trial results. Their trust in the government institutions responsible for implementing the trial declines, however, particularly with regards to perceptions of competence and integrity.

- Education can partly restore this loss of trust. Members of the public who receive information explaining the value of policy experiments and the importance of learning from unexpected results partially report smaller reductions in trust.

This research highlights a significant challenge to advancing evidence-based policymaking at scale: the need to manage both policymakers’ and citizens’ expectations of policy experimentation. The authors propose communication strategies that prepare policymakers for all potential outcomes and emphasize the valuable lessons trials can provide, regardless of their results. Finally, the authors recommend conducting future evaluations to assess the effectiveness of educational interventions that leverage policy experiments to enhance government accountability and foster trust among citizens.