- About

- Network

- Research Initiatives

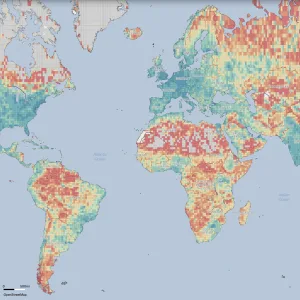

- Big Data Initiative

- Chicago Experiments Initiative

- Health Economics Initiative

- Industrial Organization Initiative

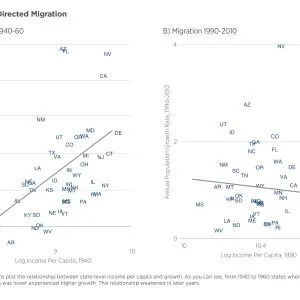

- International Economics and Economic Geography Initiative

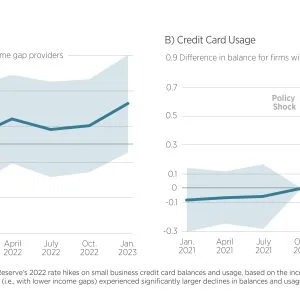

- Macroeconomic Research Initiative

- Political Economics Initiative

- Price Theory Initiative

- Public Economics Initiative

- Ronzetti Initiative for the Study of Labor Markets

- Socioeconomic Inequalities Initiative

- Research Initiatives

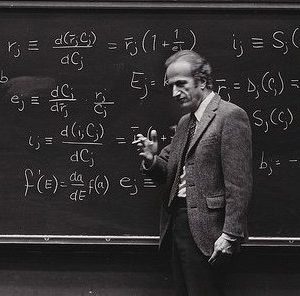

- Scholars

- Research

- Evaluating Recent Crackdowns on Disability Benefits: Effects on Income and Health Care Use in AustraliaManasi Deshpande, Greg Kaplan, and Tobias Leigh-WoodThe Law and Economics of Lawyers: Evidence from the Revolving Door in China’s Judicial SystemJohn Zhuang Liu, Wenwei Peng, Shaoda Wang, and Daniel XuThe Invention of Corporate GovernanceYueran Ma and Andrei Shleifer

- Insights

Videos

BFI Youtube Channel

- Events

Upcoming Events

- News