Parents are crucial to children’s educational success, but the role of parental education in fostering academic excellence remains underexplored. In economic models of human capital formation, parents serve as a key input in the education production function. Yet we know surprisingly little about how this translates into children’s prospects for reaching the highest levels of achievement.

In this paper, the authors document educational disparities between first-generation and continuing-generation students in the likelihood of reaching the highest levels of academic achievement (or “excellence”). They use statewide administrative data from North Carolina covering all public school students from third grade through the end of high school, including information about college readiness and intentions to pursue higher education. The authors define academic excellence as reaching the top decile of performance on North Carolina’s End-of-Grade (EOG) assessments in mathematics and reading, and the excellence gap as the percentage point difference between continuing-generation and first-generation students’ rates of reaching this top performance level. The authors establish five empirical facts:

1. Large excellence gaps emerge by 3rd grade and persist through high school

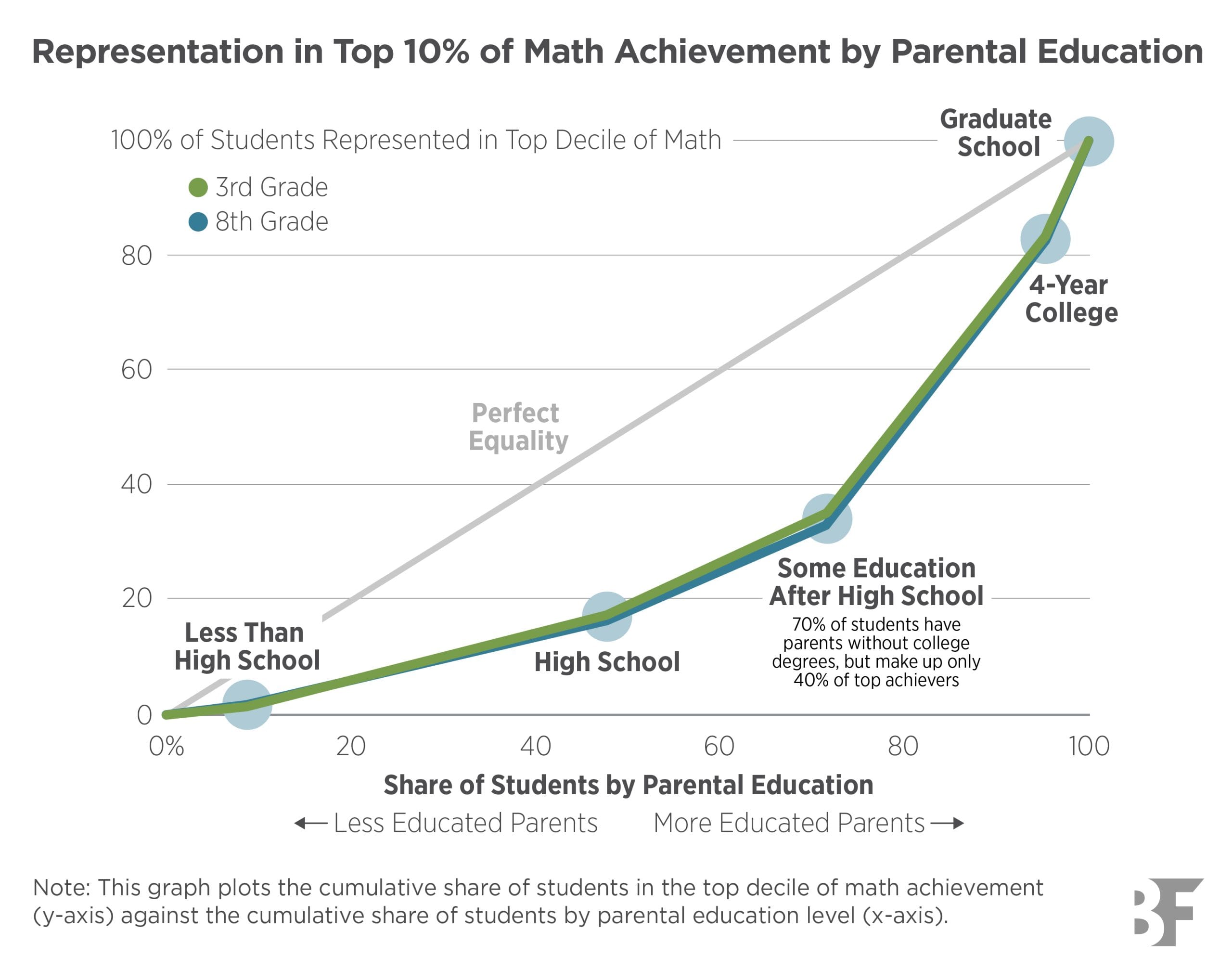

By 3rd grade, first-generation students are 17 percentage points less likely to reach excellence in math than continuing-generation students—a gap of 76% from the continuing-generation average of 22.5%. This disparity grows to over 19 percentage points (80%) by 8th grade. Remarkably, first-generation students make up around 70% of the student population but represent less than 40% of those who reach excellence.

These gaps persist into high school measures of college readiness. Continuing-generation students are about 35 percentage points more likely to take any AP exam, over 10 percentage points more likely to score a 5 on an AP exam, and 20 percentage points more likely to score in the top decile of the SAT. They are almost twice as likely to have plans to attend a 4-year college.

2. First-generation students are less likely to enter and remain in the top decile

Using longitudinal data, the authors find that over 60% of continuing-generation students who were excellent in 3rd grade remain excellent in 8th grade, while less than 40% of first-generation students maintain excellence. Even among students who reach the top decile, first-generation students have lower average test scores and are more likely to be in the 90-94th percentiles, while continuing-generation students cluster in the 96-99th percentiles. At every percentile of 3rd grade achievement from 90 to 99, continuing-generation students are at least 10 percentage points more likely to remain in the top decile.

3. Excellence gaps are universal across demographics and schools

The first-generation excellence gap exists across all demographic subgroups, though with important variations. For Asian students, the gap is at least 10 percentage points larger than for White students in 3rd grade, widening to over 15 percentage points by 8th grade. The gap for low-socioeconomic status students is about 10 percentage points lower than for higher-SES students.

Across North Carolina schools, while the average excellence gap is around 14 percentage points, this widens to 22-24 percentage points for schools in the 10th percentile of the excellence gap distribution. Importantly, less than 3% of all schools exhibit a positive excellence gap—meaning in nearly all schools, first-generation students reach excellence at lower rates than continuing-generation students.

4. Socioeconomic status and school quality explain only around one-third of the gaps

Through decomposition analysis, the authors find that first-generation differences in economic disadvantage explain about 20% of the excellence gap, while differences in schools attended explain almost 12%. Combined, these observable factors account for roughly one-third of the gap, leaving nearly 70% unexplained. This suggests the role of other important factors, particularly information gaps and the deeper challenges rooted in parental human capital.

The patterns differ when considering other parts of the achievement distribution—schools explain a smaller portion of differences in reaching above median or bottom 10% achievement than for the excellence gap, while socioeconomic status explains a much larger portion.

5. Teachers vary in their effectiveness with first-generation versus continuing-generation students

The authors find considerable variation in teacher effects on elementary school excellence. A teacher with one standard deviation higher effect on math excellence increases a student’s rate of reaching excellence by 3 percentage points. Critically, while teacher effects on first-generation students correlate highly with effects on continuing-generation students for math (0.8), the correlation is lower for reading (0.4), suggesting certain teachers have comparative advantage for helping first-generation students reach excellence.

These elementary school teacher effects carry long-term consequences. A teacher with one standard deviation higher effect yields 8 percentage point increases in taking an AP exam, 3 percentage points in achieving a score of 5 on an AP exam, and 5 percentage points in planning to attend a 4-year college.

Policy Implications

These findings reveal that excellence gaps reflect deeper challenges rooted in parental human capital that manifest early and compound over time, rather than merely consequences of socioeconomic disadvantage or school quality differences. The results suggest several policy directions:

Early intervention is crucial. Since excellence gaps emerge by 3rd grade and persist, policies should target elementary years rather than focusing solely on college access. This includes enhanced academic enrichment programs to build the cultural and informational capital typically provided by continuing-generation parents.

Teacher allocation matters. The finding that some teachers exhibit comparative advantage for first-generation students highlights opportunities for targeted professional development and strategic teacher assignment policies.

Look beyond average outcomes. While much focus has been placed on bringing struggling students to proficiency, these findings highlight the importance of ensuring that all students—regardless of their parents’ educational background—have equal opportunities to reach their full academic potential.