Decades of research on regime type and development have debated whether autocracies grow more slowly than democracies. This paper highlights a critical oversight: not all autocracies are alike. Some are institutionalized, with power constrained by parties, legislatures, or militaries—like Mexico under the Institutional Revolutionary Party or Singapore under the People’s Action Party. Others are personalist, where rulers wield unchecked authority—like Mobutu’s Zaire or Saddam’s Iraq.

In this paper, the authors study the role of this institutional variation in generating divergent economic outcomes. They extend the dynamic panel design of Acemoglu et al. (2019), analyzing GDP and regime-type data for up to 179 countries from 1960 to 2010. They estimate how GDP per capita growth differs across democracies, institutionalized autocracies, and personalist autocracies using eight different autocracy classifications (including Freedom House, Polity, and V-Dem) paired with six distinct measures of personalism.

These personalism measures include direct indicators of power concentration—such as Gandhi and Sumner’s measure of control over political offices and freedom from military/party constraints, and Geddes, Wright and Frantz’s categorical classification of personalist regimes—as well as broader institutional measures like Polity’s executive constraints, V-Dem’s presidentialism index, and Henisz’s veto players measure.

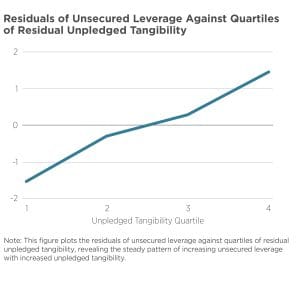

To assess causal effects, the authors employ a dynamic two-way fixed effects model controlling for country and year fixed effects, plus four lags of GDP per capita to account for pre-existing income dynamics and the tendency of political transitions to accompany economic downturns. This strategy helps isolate the impact of regime structure from confounding factors such as economic shocks or endogenous transitions. The authors find the following:

- Whether a personalist penalty emerges depends on the specific measure of personalism used, but when it does appear, the effect is typically concentrated in personalist dictatorships rather than being uniform across all autocracies.

- The growth performance of institutionalized dictatorships shows no consistent pattern of underperforming relative to democracies across most specifications.

- The mechanisms behind any personalist penalty appear to involve some combination of lower total factor productivity, reduced private investment, worse public goods provision, and greater conflict, though the particular relationships vary depending on the measure of personalism employed.

- These general patterns hold across different GDP data series, various personalism indicators, and alternative sample restrictions, including excluding extreme growth episodes and planned economies.

Not all autocracies threaten economic development equally. Democracies and institutionalized autocracies may support growth through credible institutions, policy stability, and checks on executive power. But where power is highly concentrated—particularly in regimes like Putin’s Russia, where institutional constraints have been systematically dismantled—economic outcomes may suffer significantly.

Recognizing potential personalist penalties is vital not only for forecasting development trajectories, but also for shaping diplomacy, aid strategies, and institutional reform efforts. The findings suggest that international engagement should focus on strengthening institutional constraints on executive power rather than simply promoting democratic transitions. For global stability and development, the critical distinction may not be between democracy and autocracy, but between institutionalized and personalized rule.